Functions are bits of code that tell R to run a set of instructions to an object (or a group of objects) and return a specific output. You could, for example write a function that tells R to calculate the 95% CI around a number based on its mean, standard deviation, and number of observations:

make_95CI <- function(mean, stdeviation, observations){

standarderror <- stdeviation/sqrt(observations)

upper <- mean + 1.96*standarderror

lower <- mean - 1.96*standarderror

output <- list(Mean = mean,

Lower95 = lower,

Upper95 = upper,

CIRange = c(lower, "-", upper))

return(output)

}

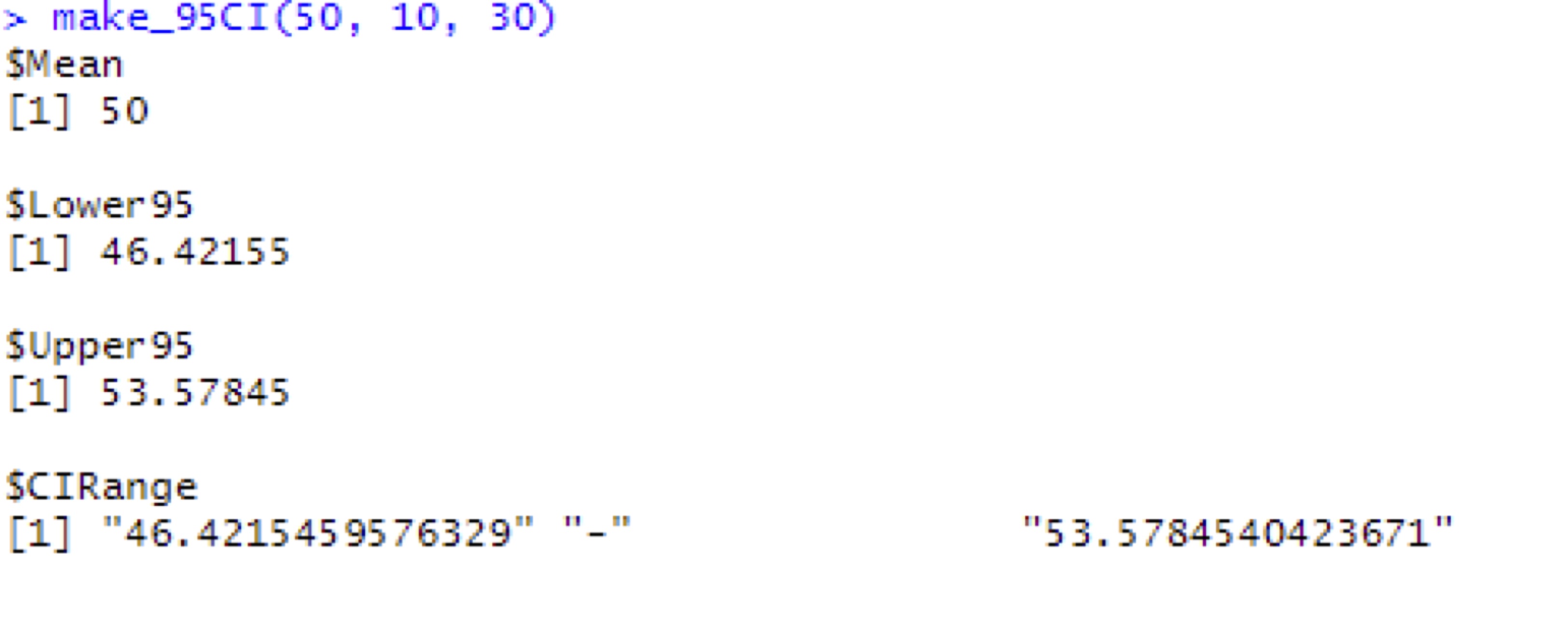

This is creating a function called “make_95CI”, and it takes three arguments: “mean”, “stdeviation”, and “observations”1. It then calculates the standard error2 and therewith the upper and lower bounds of the interval. It then creates an object called “output”, which is a list containing three objects: “Mean”: the mean3; “Lower95” and “Upper95”: the lower and upper bounds of the interval; and “CIRange”: an object expressing the range. Let’s look at an arbitrary example where we want the 95% Confidence Interval around a mean of 50, with standard deviation 10 and a sample size of 30 observations:

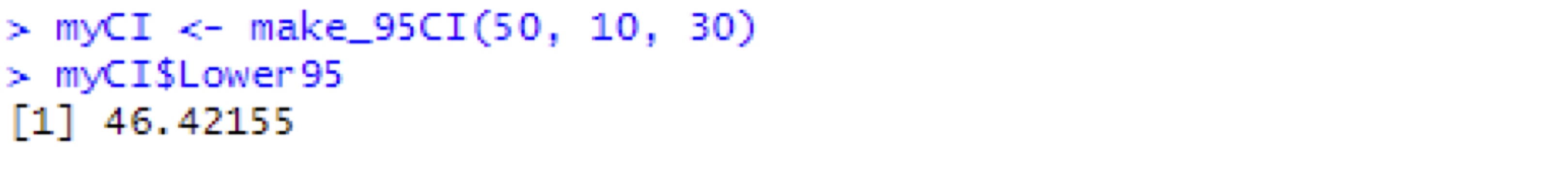

Lists have the useful property of having objects you can call by name. So if I just wanted to know the lower bound of the interval, I could do so really easily:

The object “myCI” contains the “output” list that is returned by the function “make_95CI”. We can ask for the item “Lower95” from “myCI” by using the dollar sign ($) character. Dataframes also have this property, but while lists can have lots of different types of data within the same object, all objects within a dataframe must have the same length.

Building functions allows us to run multiple steps from a single line of code, which is particularly useful when we have to repeat some process or set of processes multiple times within the same program. It’s also handy if you have a process that you use often between different programs. You can load your function into your global environment, specify whatever inputs are relevant to your program, and you’re in business.

-

An important note: when you call this function, R will preserve the order of the arguments but the names can be whatever you want. “mean” “stdeviation”, and “observations” can be numbers like in the example in this post or they can be objects with whatever name you want ↩

-

Interesting to note: “standarderror” only exists WITHIN the function. If you run the function and then try to call “standarderror”, R will tell you there is no such object. Once the function has run, “standarderror” disappears. If you want an object to live outside of the function, you have to “pass it” to the Global Environment, which is what the “return” statement is for. ↩

-

Note the capitalization. This is my personal convention to distinguish “Mean” (an output) from “mean” (an input). You don’t have to use capital letters, just make sure you are keeping track of which objects are what or you can confuse yourself and anyone else trying to use your function. ↩